For a few days in October 1993, if you were interested in journalism and technology, Raleigh, North Carolina was the place you had to be.

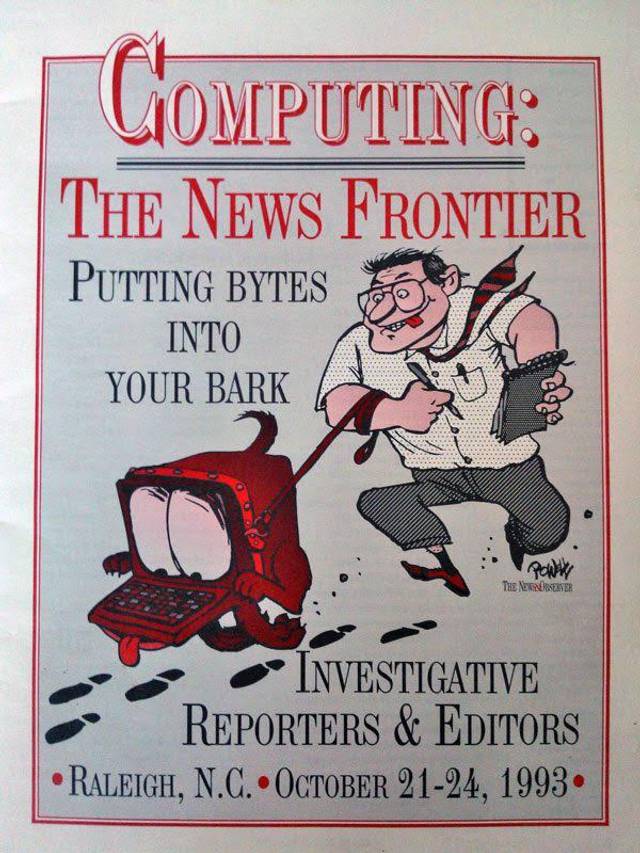

The first Computer-Assisted Reporting Conference offered by Investigative Reporters & Editors brought more than 400 journalists to Raleigh for 3½ days of panels, demos and hands-on lessons in how to use computers to find stories in data.

That seminal event will be commemorated this week at the 25th CAR Conference, which starts today in Newport Beach, California. While I’m unable to attend this year, I thought it would be a good time to assemble some memories and take note of the significance of those few days in Raleigh.

“That weekend changed my life,” was how attendee Paul Adrian put it a few years later when he wrote about the Raleigh conference (PDF) for the Poynter Institute.

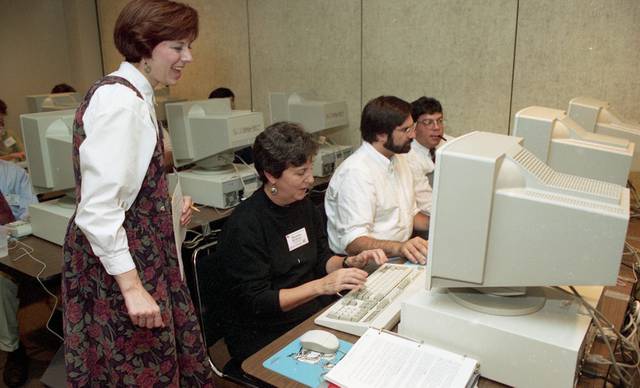

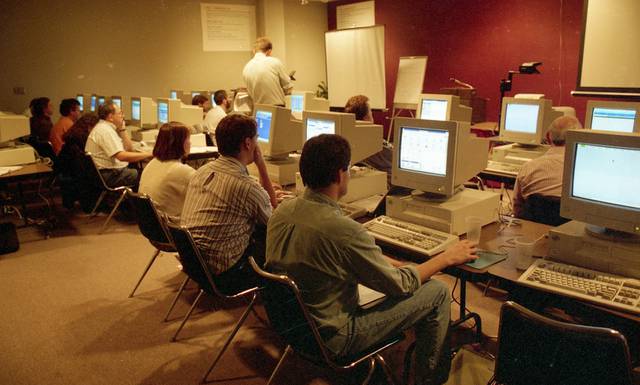

I myself was in Raleigh because I was an early adopter of CAR – now more commonly called “data journalism.” I wrote the hands-on lessons teaching journalists how to use spreadsheet software, and helped prepare other volunteer instructors to teach them. The attendees crammed into hotel meeting rooms to do my spreadsheet exercises, and learn many other data tools, on dozens of PC’s that IRE had rented for the occasion. (Important note: The Raleigh event was not the first journalism conference devoted to CAR - others had been held in Indianapolis in 1991 and 1992.)

Other 1993 tech developments

It wasn’t only CAR that made the conference noteworthy. In journalism and tech, 1993 was significant for other reasons.

News organizations were rushing to start publishing online through services called Prodigy, Compuserve and America Online, which you accessed through your phone line and a noisy little box called a modem. According to Dave Carlson’s Online Timeline, those services had 3.9 million subscribers as of September 1993 – about one in 25 U.S. households.

But the most historically significant tech events of 1993 took place in Champaign, IL, home of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications. In February, NCSA released the first version of the Mosaic browser, for the UNIX operating system. By the time of the Raleigh conference, versions of Mosaic had also been released for Windows and Macintosh. Mosaic was the first widely available Web browser that allowed images to be viewed on the same page as text.

Sometime during the conference, I remember someone showing me a Web page on the Mosaic browser – and also the HTML code that generated the page. (Reconstructing the history, I am now questioning my memory. It’s possible my HTML experience took place at the 1994 CAR conference [PDF of the program] in San Jose, which I also attended, rather than in Raleigh.)

Whenever it was that I saw HTML for the first time, it was a pivotal moment for me. The online services – AOL, Compuserve and Prodigy – hadn’t seemed that interesting to me because they mostly displayed text, with some tiny images, in a rigid display template. Web pages seemed like a much more appealing way to design and present content. I guessed, correctly as it turned out, that the Web would end up being the way we would publish news online.

A number of us who attended the Raleigh conference would ultimately end up using technology to distribute journalism rather than to analyze data to produce stories. In 1995, I would become the first online director for The Miami Herald. Other panelists and instructors at the conference who’d take a similar path included Scott Anderson of the South Florida Sun-Sentinel (and later Tribune Interactive) and Dan Woods, who became director of editorial technology for Time Inc. New Media.

Why Raleigh?

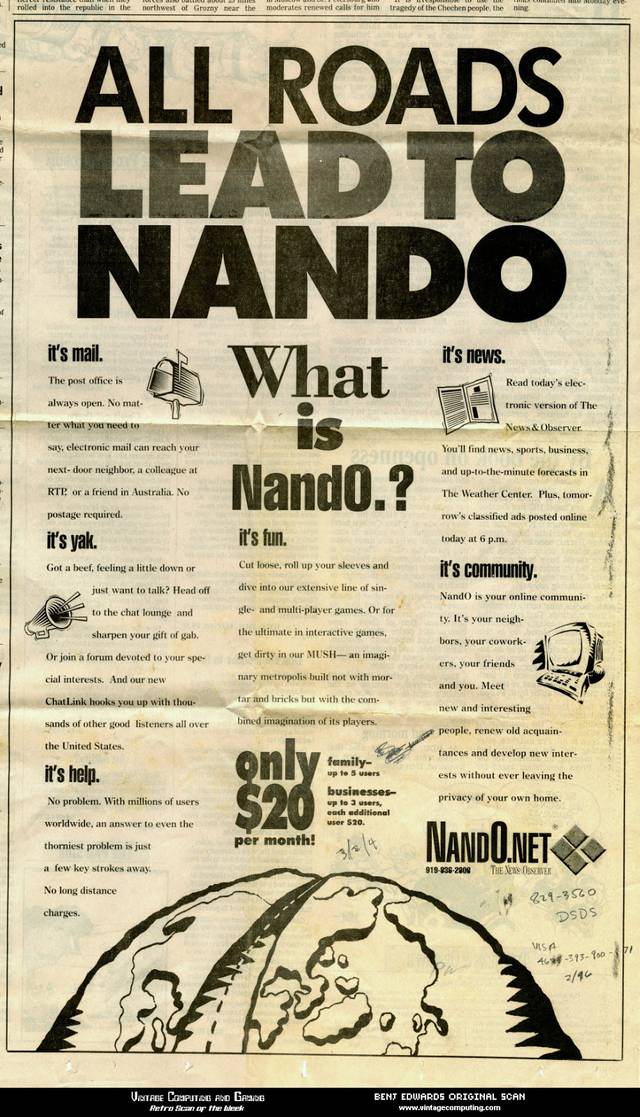

Raleigh was an interesting place in 1993 because its hometown newspaper, the News & Observer, at that moment might have been the most technologically sophisticated news organization in the world.

The News & Observer established itself as an Internet Service Provider (ISP) in the Raleigh area in 1993, and began selling Internet access. Initially, the service offered access to now obscure Internet services Gopher, WAIS, Lynx and Telnet. But by 1994, the paper had established the Nando Times, one of the first news publications on the World Wide Web.

Meanwhile, inside the newsroom, the newspaper had reorganized itself to prioritize stories driven by data analysis. Ace investigative reporter Pat Stith was given a multi-year assignment to build the newsroom’s capacity to work with data. The newspaper built a best-in-class news research staff and hired a database manager whose job was to acquire government databases and make them accessible to reporters in the newsroom. It even offered interest-free loans to allow staff members to buy a PC. (In those days, a computer to do this kind of work cost $2,000 to $3,000.)

In 1993, according to Teresa Leonard, the newspaper produced 82 stories, large and small, driven by data analysis. [Leonard’s memories, as well as those of other data journalism pioneers, were captured in a 1999 Poynter Institute report called “When Nerds and Words Collide: Reflections on the Development of Computer Assisted Reporting.”]

All of this was driven by the paper’s editor, Frank Daniels III, scion of the family that long owned the newspaper. (It would be sold to McClatchy in 1995). Daniels believed, correctly, that technology would transform the news industry, and was determined that the paper would lead the transformation rather than be disrupted.

“I recall passing Frank Daniels III in the stairway at one point and thanking him profusely for his moral and financial support for this now-historic event in CAR history,” Anderson told me via Facebook this week.

Our technology was primitive

Looking back from 2019, it’s hard to overstate how primitive the technology was at the first CAR conference.

Large government databases usually arrived on “nine-track tapes,” which the most sophisticated newsrooms could extract data from using a huge tape drive and Nine-Track Express software developed by CAR pioneer Elliot Jaspin and the aforementioned Dan Woods.

Many newspaper newsrooms had no personal computers, relying on “dumb terminals” for editing and producing the paper every day. Journalists who wanted to work with data often had to get started by buying their own computer and doing the number-crunching at home. Using a PC was so novel that to say “he routinely uses computers” – quoting from the bio of one Raleigh panelist – was a badge of pride.

We were such nerds that we would brag about our PCs – especially the size of our hard drives.

We were such nerds that we would brag about our PCs – especially the size of our hard drives. The speaker bios in the Raleigh conference program provided details on the data-driven stories they’d done, as well as the computers they worked on.

For example: “He works on a 486 PC with a 200 MG hard drive and 8 MG of RAM.” To put that in perspective, a low-end iPhone with 64GB of storage has more than 300 times the capacity of that computer. (If you’re wondering, “486” was the speediest Intel chip available at the time in a consumer PC.)

Looking at the conference program, it’s clear that the 1993 speakers and attendees were overwhelmingly male. My friend Shawn McIntosh likes to joke that the first “women of CAR” meetup could have taken place in her conference hotel room. By the 2016 conference, when attendance exceeded 1,000 for the first time, there were hundreds attending the “women of CAR” gathering. (Though it’s fair to say that the data journalism field, like all of journalism, still has a long way to go with regard to diversity and inclusion.)

People who had what we then called “computer skills” were so unusual in news organizations that they might be called upon to apply those skills in multiple ways.

People who had what we then called “computer skills” were so unusual in news organizations that they might be called upon to apply those skills in multiple ways. Journalists doing data analysis in reporting sometimes also worked on market research projects or digital publishing initiatives.

In those days, most “data analysis” was quite simplistic. There was very little advanced statistical analysis, mostly just sorting and grouping records, and no machine learning or Python or JavaScript. We relied on desktop spreadsheet and database software – and in those days, there was something of a religious war between the spreadsheet devotees and the database geeks. (My religion happened to be spreadsheets.)

“Data visualization” in 1993 meant creating graphics for print publication; we couldn’t have imagined the world of news applications and interactive, exploratory visualizations that became possible thanks to Web browsers, cheap data storage (thanks, Amazon Web Services!) and Javascript libraries.

Who was there

Despite the crude technologies we were using, the Raleigh conference brought together a remarkable group of people who had influential careers. Just a few examples in alphabetical order (apologies to the many worthy attendees I left out).

- Sarah Cohen: then a reporter for the Tampa Tribune, now the Knight Chair for Data Journalism at Arizona State University (and shared a 2002 Pulitzer Prize while at the Washington Post)

- Paul D’Ambrosio: then an investigative reporter for the Asbury Park Press, now executive editor there

- Stephen K. Doig: then associate editor for research at the Miami Herald (where his data analysis drove the paper’s Pulitzer-winning examination of the impact of Hurricane Andrew); later a journalism professor at Arizona State.

- Mary Pat Flaherty: then metro projects editor at The Washington Post (and already a Pulitzer winner for work she did at the Pittsburgh Press), now a reporter at the Post.

- Dan Gillmor: then tech columnist for the Detroit Free Press; later a San Jose Mercury News columnist and blogger, where he became an influential voice on citizen journalism and media literacy and wrote two important books.

- Brant Houston: then database editor for the Hartford Courant, later the long-time executive director of IRE, now a journalism professor at the University of Illinois.

- Jennifer LaFleur: then research analyst for the San Jose Mercury News, later CAR director for the Dallas Morning News and Pro Publica (and a Pulitzer finalist for work at Reveal/Center for Investigative Reporting).

- George Landau: then manager of information technology for the St. Louis Post Dispatch, later the founder of NewsEngin, a technology provider to news organizations.

- Shawn McIntosh: then assistant city editor for the Dallas Morning News; now editorial director for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Phil Meyer: then a professor at the University of North Carolina and author of the influential books Precision Journalism and The New Precision Journalism; now emeritus professor at UNC.

- Judy Miller: then assistant city editor for the Miami Herald; later became its managing editor for investigations.

- Nora Paul: then library director for the Poynter Institute, later head of the Institute for New Media Studies and the Minnesota Journalism Center at the University of Minnesota.

- Melanie Sill: then deputy metro editor for the News & Observer; later executive editor there, editor of the Sacramento Bee and VP/content for Southern California Public Radio.

- Pat Stith: then an investigative reporter for the News & Observer, where his work earned a Pulitzer Prize in 1996; he retired in 2008.

I can identify at least nine Pulitzer winners or finalists among the conference speakers and panelists. I’m sure the actual number would be much higher than that. And I count at least 10 people who, like me, went on to teach college journalism, which means the attendees have continued to shape later generations of journalists.

What—and who—have I missed?

To assemble this information about attendees, I relied mostly on the list of 68 speakers, panelists and instructors included in the Raleigh conference program. I don’t have a complete attendee list, and if one still exists, it is buried in the IRE archives.

But as someone who majored in history, I am well aware that memories can be faulty and documentation can disappear.

So, If you have memories of the 1993 Raleigh conference, please share them on Twitter with the hashtags #NICAR19 and #CAR93memories. Or email me at richgor - at - northwestern.edu. If there are enough interesting memories, I’ll write a follow-up piece.

If you want to delve more deeply into the history of CAR, here are a few places to start:

- “Pioneers, Playboy & 5 decades of precision journalism” (video, 62 minutes including Q&A), Shawn McIntosh’s keynote speech at Computation+Journalism Symposium 2017.

- “The History of CAR,” 2015 article by Jennifer LaFleur for The IRE Journal

- When Nerds and Words Collide, a collection of essays assembled by the Poynter Institute in connection with a 1999 convening of CAR pioneers.

- “CAR through the ages: What I learned from collecting every single NICAR program since 1990,” 2017 lightning talk (in rhyme!) by Christine Zhang.

- Christine Zhang’s archive of CAR Conference programs.

- The 1993 CAR conference program (PDF)

Final reflections

Counting Raleigh in 1993, I have probably attended half or more of the 24 previous CAR Conferences. It’s the place my journalism tribe comes together, so I hate to miss it. I’m particularly sorry not to be able to attend the Friday afternoon (March 8) panel entitled “25th CAR: What a ride it’s been!”

The list of possible “special guests” at that panel is amazing and includes a lot of the people I mentioned above. I wish I could be there to share my memories, connect with old friends and make some new ones.

While I can’t be there in person, I wrote this piece to serve as my contribution to the discussion. I hope you’ve enjoyed this trip back through time.

Rich Gordon, Medill School professor and co-founder of the Knight Lab, launched Medill’s digital journalism master’s program and currently directs Medill’s MSJ specialization in media innovation and entrepreneurship. He also created the Knight Foundation-funded scholarship program that has enabled 15 people with software development backgrounds to earn a master’s degree in journalism at Medill.

About the author