This story is part of a series on bringing the journalism we produce to as many people as possible, regardless of language, access to technology, or physical capability. Find the series introduction, as well as a list of published stories here.

“Our audience” is a phrase that has been used so much during my time in various newsrooms that it has sometimes become as soothingly monotonous as white noise. "Who is our audience?" "How do we best serve our audience?" To the first question, the answer could be geographic. It could be racial. Or, in a rather cold-hearted but pragmatic response, it could be as simple as “whoever can pay the bills.”

I grew up in Athens, Ohio, a county in the foothills of Appalachia where many could not pay the bills, much less the bills of a newsroom. About 30 percent of the population was in poverty as of 2014 and I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how newsrooms can do a better job of making information more accessible to low-income audiences traditionally outside their reach, especially since this election season is proving that they — surprise! — have a voice.

For example, I’m thinking about a demographic of people who were my neighbors growing up — those without access to internet. I found out from Lindsay Shanahan, executive director of Connect Ohio, an advocacy group for increased broadband access and adoption in the state, that while upwards of 98 percent of Ohioans have basic broadband service (defined by Connect Ohio to be 3 Mbps to download and 768 Kbps to upload), the majority of the remaining two percent are concentrated geographically in Appalachian Ohio. That means that a whole region does not have (or has limited) access to the internet or the information it provides.

I know from experience that internet is not to be taken for granted in Appalachian Ohio. It’s a hilly and woodsy region, so mobile providers have a hard time establishing the line-of-sight necessary for data transmission. And it’s rural and sparsely populated, so broadband providers are less likely to recover costs to build infrastructure (and expensive infrastructure, because of the hills and the trees) for so few people. For news organizations, this is more than just a loss of an audience or paying subscribers — it’s a loss of perspective in the stories we tell.

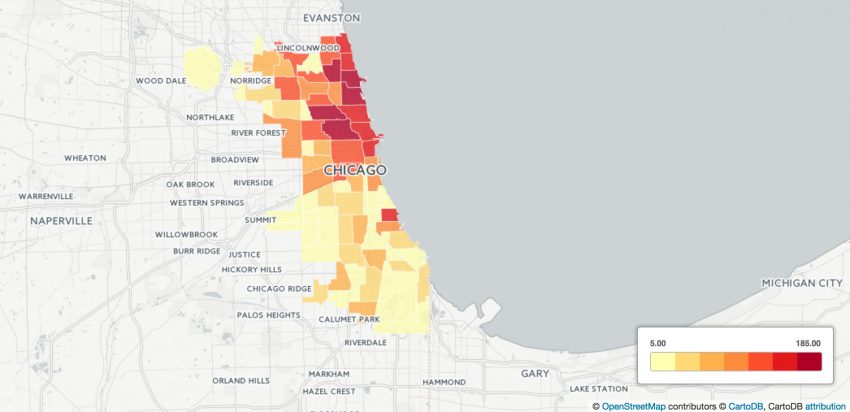

No organization likely understands the gravity of a missing audience more than Curious City, a WBEZ-Chicago program whose stories come in the form of answers to questions their audience submits, like, “How do they clean ‘the Bean’?” or, “Where does the Chicago accent come from?” In other words, Curious City’s editorial content depends directly on the participation of its audience. And editor Shawn Allee realized that most of its questions were coming from listeners in the areas WBEZ does best in: highly-educated or affluent areas like Evanston, Oak Park, Lakeview, and parts of of Hyde Park.

“Whatever journalistic value you want to put out in the world, you want to provide it for a certain audience. For WBEZ’s case, it’s the Chicago area,” Allee said. “A problem, though, is that your audience is always smaller than your mission. One way or another, someone is not available to participate because they don’t know you or because they don’t hear your appeal all the time.”

With a grant from the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, Allee and his team are figuring out the best way to add to their audience. They geocoded past audience-submitted questions, and identified some key community areas to focus on for outreach — broadly speaking, the West and South Sides and select suburbs. Each neighborhood is unique, and some areas that are very similar in terms of socio-economic status, race and educational levels — like DuPage County and Evanston — have very different listening styles.

Curious City’s attack strategies? In-person communication, like interviewing people at a park, social media ourteach, and partnerships with local organizations.

It’s too soon to know which strategy is best, but Bill Healy is on it. A contract producer on this project and a regular WBEZ freelancer, he went out to the southern suburb of Aurora to install question boxes in public libraries and even at a popular local brewery where people are most likely to take time to write.

“A place like a cafe, or a restaurant, where people are sitting and talking, there’s a free flow of ideas,” Healy said. As for libraries, “The mission of the library is in line with Curious City — facilitating curiosity. That’s where their values are, and that’s where our values are."

That strategy is not unique to Chicago. Connect Ohio's Shanahan speculated that in Ohio, partnerships with libraries and community organizations like Boys and Girls Clubs are key for media organizations who want to reach out to traditionally underserved communities.Tech is only one of the many tools we have, and that it only goes so far on its own when it comes to connecting a to community.

“Of those who have it, the majority have it to read online news outlets, but for those who don’t, the question becomes where are they going to get (it),” she said. According to a 2014 survey, 67 percent of Ohioans say they use the internet to read the news. “Are those facilities providing access to those materials?”

Of course, solving WBEZ’s or Ohio’s problems isn't as simple as putting a box in a library. When Northwestern professor Eszter Hargittai joined us for our weekly Lab Lunch this quarter, she showed us how low-income internet users tend to use the internet for “recreational purposes,” and fewer low-income internet users than their wealthier counterparts are on social media, especially Twitter, because their communities don’t exist on those sites. But she suggested that online sites could make their work more accessible through design, as Facebook did with the privacy dinosaur to help all users navigate their privacy settings.

I never answered the second question I posed at the beginning of this blog post - “How do we best serve our audiences?” Certainly, serving or redefining one’s audience is difficult because it means connecting with them in ways that mean learning a new figurative (or sometimes literal) language. But for those of us who report, write, design and build news websites, it is time to acknowledge that tech is only one of the many tools we have, and that it only goes so far on its own when it comes to connecting a community.

About the author