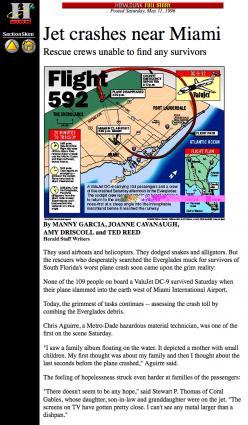

Twenty years ago today, The Miami Herald went live on the World Wide Web, unveiling its website a couple of weeks ahead of schedule because of breaking news: the crash of a passenger airplane into the Everglades about 25 miles northwest of The Herald's building on Biscayne Bay.

At the time, when newspaper people talked about online publishing, we called the website "another edition of the newspaper" -- not an entirely different platform with new capabilities. But people like me, the first generation to lead local online publishing operations, learned quickly how the Web was different. In this post, I'll run through 10 of the lessons I learned as The Herald's online director -- but first, a little background.

When ValuJet flight 592 crashed into the Everglades on a Saturday afternoon, killing more than 100 people, I was in the office catching up on some paper work. The planned launch of what we then called HeraldLink was still a couple of weeks away, but the small team I had assembled was already working with the paper's print and Web publishing systems to post content to a private server and debug problems we were finding.

My first reaction when the plane crash happened was to regret that I wasn't involved in the newsroom any more -- a sentiment that may give you a sense of how divorced the online operation was from the newspaper in those days. My second reaction was to regret that the website hadn't launched yet.At the time, when newspaper people talked about online publishing, we called the website “another edition of the newspaper” — not an entirely different platform with new capabilities.

But then my news instincts kicked in. We were already producing a website; it just wasn't unveiled to the public yet. And it was hard to imagine a bigger story happening in our back yard. I decided that we should go live with the plane crash coverage and as much of the website as we could. Our designer made some "sneak preview" icons for pages that weren't finished, and I called in the online team to prepare our coverage of the plane crash.

If you want to know what a newspaper website looked like in 1996, I had the foresight to save a complete copy of the site the next day - and here it is.To see the site as we intended, you'll want to narrow your browser window -- this site was built for a 640-pixel-wide screen. If you click very deeply, you'll find missing images and broken links, but that's exactly the experience we offered 20 years ago when we launched ahead of schedule.

Before my role with The Herald's website, I had pursued a fairly traditional path through the newspaper industry -- from reporter to editor, from smaller papers to larger papers. Along the way, I had become an early practitioner of data journalism (what we then called "computer-assisted reporting"), which my bosses saw as evidence I had the blend of journalism and technology skills needed to launch The Herald online.

I thought I was as prepared as any journalist could be to take on this new challenge. But it wasn't long before I realized how different online journalism and publishing were from their print counterparts. Here are some of the lessons my team and I learned in those early days on the Web.

-

A website is software, not just a bunch of digital pages

The Herald's website launch was driven -- and constrained -- by the Web publishing strategy of our parent company, Knight-Ridder. A decade after losing millions on its Viewtron "videotext" project, Knight-Ridder sought to publish its newspapers' content on the Web as efficiently as possible -- through automated scripts that would convert newspaper stories to Web pages, organized by topic. This approach presumed that newspaper stories would have significant value for online readers and that a small online staff would be able to do whatever else was need to build an online business.

With my data journalism experience, I felt certain that we would need computer programming capabilities, so I included a developer as one of the first five people I hired. For that decision, I was yelled at by the head of Knight-Ridder's Internet business, who said we wouldn't need our own technology capabilities because the parent company would provide what we needed.This approach presumed that newspaper stories would have significant value for online readers and that a small online staff would be able to do whatever else was need to build an online business.

Our developer more than demonstrated his value, building technology that improved upon the Knight Ridder publishing tools -- including a project that enabled The Herald to include company logos in our online classified ads, which generated significant new revenue for the newspaper and our web business. Meanwhile, our sister paper in Philadelphia consistently outperformed all the other newspapers in the company -- in traffic, revenue and innovation -- because they built their own technology instead of using Knight-Ridder's. (The tech leader in Philadelphia, a young developer named Rajiv Pant, would later move on to lead engineering teams at Cox Media Group, Conde Nast, The New York Times and Tribune Publishing.)

-

The business model would need to be different

Knight-Ridder's digital strategy was, essentially, to replicate the business model it was familiar with: a package consisting of content and advertising, with customers paying for delivery. The strategy relied on Knight-Ridder's investment in an Internet service provider (InfiNet), which enabled its newspapers to offer not only content and advertising, but Internet access in its markets. The idea was that if you bought your Internet access from The Herald, access to its news content was included -- but if you got your Internet access from another provider, you'd pay to access the newspaper website.The Internet access business was never successful in metropolitan markets like Miami where people had many choices in Internet providers, though it worked a little better in Knight-Ridder's smaller markets. And most Knight-Ridder papers never implemented the subscription wall for non-customers of the Internet access business -- which left advertising as the primary revenue opportunity.

It became clear very quickly that online advertising wouldn't work the way print advertising did. Knight-Ridder wanted us to sell banner ads, but it was impossible to sell banner ads to a business that didn't have a website, which was the case for most local companies in 1996. We decided that we needed to get into the website development business, which for a time generated a substantial share of our online revenue.

-

People use websites differently than print newspapers

When we launched HeraldLink, we were particularly proud of our unique "Section Skim" buttons in the navigation bar, which made it easy for users to click through the site from one section to the next. This was based on our assumption that many readers would move through the newspaper from beginning to end, the same way they skimmed through a print newspaper.The buttons never proved to be very popular -- regular visitors accessed most of our content through the home page or the sports section. When we redesigned the site a couple of years later, the "Section Skim" buttons disappeared.

-

The popularity of online content wasn't under our control

The articles that attracted the biggest audiences, we were surprised to discover, weren't necessarily the ones that we gave the most prominent treatment on the site. A link from a high-traffic portal (Yahoo.com) or aggregator (Drudgereport.com) could instantly drive a story -- even one we didn't consider one of our best --to the top of our pageview list. It was an early indicator that audience attention on the Web is driven by links more than a site's editorial judgment. -

On the web, our competition was ... everyone

The story that inspired the rush to push the first Miami Herald site to production. A year or two after launch, at a meeting of online managers from all the Knight-Ridder papers, corporate leaders showed us research

data on the popularity of websites in local markets. Over the course of a month, our newspapers' websites were visited by 15 to 20 percent of the Internet audience in each of our markets, while the most popular sites (for instance, Yahoo!) were visited by 80 to 90 percent of Internet users.Like most of my fellow web managers, my initial reaction was that Yahoo! wasn't our competition -- we were local publications, and Yahoo! was a national (or international) portal. But upon reflection, we realized that the online audience wasn't segmented according to geography, and the fact that most local Internet users didn't visit our site even once in a month was a big problem.

-

Ideas are easy. Execution is hard.

When I applied for the job as The Herald's online manager, I wrote a long document full of ideas about what The Herald could do on the Web. Some were obvious (a searchable database of event listings, a variety of email newsletters), while others were more creative (a site focused on Latin American music, a section keeping tabs on celebrities visiting South Florida).In practice, we never actually delivered on any of these ideas in the four years I ran the website. We tried to build the entertainment guide and a separate site geared to South Florida tourists, but we never really got them off the ground. We simply lacked the staff resources -- especially, the project management and programming talent -- needed to get these ideas launched. This meant that our sites relied heavily on the same news content that appeared in print -- the same content that only 15 percent of our local audience looked at even once in a month's time.

-

The hardest thing about online news is knowing when to stop.

Until I led an online news operation, it never occurred to me how much the newspaper's once-a-day publishing cycle defined the way its journalists worked. When news broke at night, it didn't matter what was happening at the scene -- the reporter had to file a story by the print deadline, based on whatever information was available. And once the presses were rolling, there wasn't much point in doing more reporting -- you'd come in the next morning and have the day to prepare a follow-up story.On the Web, though, there was always more you could do -- you could update the story after the print deadline, add more background or related links, improve the packaging and presentation. This was, after all, a big part of what made the Web such a powerful publishing platform, but it made for absurdly long hours for our small team of online producers.

-

We had to build a new culture.

As someone who'd spent my entire professional career in newspaper newsrooms, I didn't realize how strong and unifying the workplace culture was in those environments. Over several generations, newspaper people had developed a common understanding of what news was, how it should be covered, what roles people played and how they should work together. While there were sometimes disagreements, our common culture allowed us to get past them and successfully produce each day's edition.The Herald's online team didn't have that shared culture. We were a new team made up of journalists, designers, developers and ad salespeople, with different ideas about what we should be doing and no history of working together in a high-pressure environment. These differences led to tension, turnover and, in a few cases, outright conflict that I was unable to mediate successfully. In hindsight, this shouldn't have been surprising -- but I came to understand the challenges startup companies have in building a shared culture where none existed previously.

-

The Web rewards depth, not breadth.

When newspapers began launching websites, they recognized that there were opportunities to capitalize on topics unique to their markets -- for instance, auto racing in Indianapolis or technology in Silicon Valley. In Miami, we decided to build deep content about South and Central America, which The Herald covered far better than other U.S. newspapers.

So we designed The Herald's website to include separate pages for Mexico, every country in Central and South America, as well as Cuba and Haiti. What we didn't realize was that while The Herald provided more news on those parts of the world than other newspapers, the paper might go months without publishing a story about many of those nations. So in our Americas section, many country pages would be led by a story that was weeks or months old.The content model for a print newspaper — a small amount of information about a wide range of subjects — was fundamentally wrong for the Internet.

There could well have been an opportunity to build a news website providing regularly updated coverage from every country in the Americas, but it couldn't be constructed solely from the content being published in a daily newspaper, even one that provided as much Americas news as The Herald.

I came to realize that the content model for a print newspaper -- a small amount of information about a wide range of subjects -- was fundamentally wrong for the Internet.

-

Newspapers couldn't win online.

As a newspaper journalist turned website leader, I was excited about the opportunities the Web offered -- as I put it in my pitch for the job -- "to protect our franchise, and to expand it." I thought the Web would enable the newspaper to reach new audiences and find new revenue sources.We did have some success. Revenue grew steadily, my staff of six expanded to almost 40, and in the last two months I was there (November and December 1999), we were profitable. But it was painfully clear to me that other companies -- ones that were born online, without the history (and baggage) that newspapers had -- were doing even better than we were. And it was also clear that newspapers were not leading the way in developing new kinds of content, functionality or business models.

Only after I came to work at Northwestern University did I come across the work of Clayton Christensen, whose book, The Innovator's Dilemma, explains why great companies fail when confronted with what he calls "disruptive technology" or "disruptive innovation" -- like the Internet, in the case of newspapers.

The problem, Christensen says, is that disruptive innovations initially produce business opportunities that simply don't appeal to the most successful companies. These opportunities don't generate enough revenue and/or profit to compare favorably to what those companies are already doing -- so new companies are the one that experiment and take the risks needed to find new business models. Most will fail, but the ones that succeed ultimately will grow to compete with, and displace, their more established competitors.

From Yahoo! and Google to the Huffington Post, Facebook and Buzzfeed, we've seen wave after wave of startup companies build successful new businesses on the Web. Newspapers, meanwhile, are just struggling to survive.

Rich Gordon dedicates this post to the small but mighty team that, despite all of the challenges outlined here, pioneered online news in Miami in 1996: Aileen Gelpi, David Hancock, Malik Karim, Laura Perez and Mike Simmons. You made miracles happen every day.

About the author