This article is a part of a series written by Knight Lab Professional Fellow Steve Tarzia documenting his work to develop a crowdsourced model to support the ongoing content creation needs of GunMemorial.org. Follow the series here.

The Pulitzer Prize awarded two weeks ago to the Washington Post’s police shootings database was a victory for everyone working on telling big stories with data. The Post’s database is a great example of structured journalism, and what I find fascinating about these projects is that they tell big stories and they evolve over time as new elements are added. It's a break from the traditional newspaper or television story that presents a collection of facts and quotes that are synthesized into a single linear narrative intended for consumption at a specific publication date. The wide open spaces of digital media allow us to present readers with a multitude of information, covering vast expanses of time and space, and allow the reader to navigate through whichever elements attract her interest.

I recently launched a publication called Gun Memorial which aggregates news stories about gun-related deaths in America and collects photographs of every victim. In my struggle to make the project a success I identified a few open questions in structured journalism:

- How can we keep readers engaged in a project that gathers new mini-stories over time, even if the aggregate story remains roughly the same? Is it reasonable to expect readers to revisit a project that re-tells the same story with new examples and data?

- How can a structured journalism project fit within a traditional publication? Does it make sense to reserve space on a news website for an "old" or already-published project that has new elements every day?

- Most readers use social media to find news articles. How should a structured journalism project distribute its updates on social media?

- Should reporters and publishers plan to foster new online communities around long-lived structured journalism projects?

- How do we justify the reporting-hours that go into maintaining such a project after it has already been "published." When does it make sense to use crowdsourcing to handle the ongoing maintenance? When are these projects "finished?"

I don’t have answers for all of the above, but I did draw some insights from conversations with reporters and publishers at some related structured journalism projects: Homicide Watch, The Counted, and EBWiki.

Fit within a traditional publication

For many traditional news outlets, a structured journalism project on an important topic can serve as a supporting resource for long-form articles on that topic. For example, The Guardian's The Counted project tracks every death by law enforcement in the U.S. The project is featured on the The Guardian's U.S. front page, and it plays an important role in their coverage of police killings. Jamiles Lartey, a reporter on the project, told me: "There is a predictable flow of incidents, but there are also noteworthy outliers, which we write long-form stories on. ... These articles are powerful because they might talk about a specific case but they draw statistics from the database to indicate the frequency of that type of incident."

Still, the project is noticeably absent from some pages. It's not featured on The Guardian's pages devoted to US News or US Policing, except in so far as they frequently write articles that highlight the project. It just doesn't fit well within the timeline format that they've chosen for the "Policing" page.'Part of Homicide Watch’s mission was explaining the court process,' Amico said. 'We allowed people to attend court dates.'

Homicide Watch Chicago serves as another example of the difficulty of fitting a structured journalism project within an traditional publication. In early 2013, the Chicago Sun-Times licensed the technology behind Homicide Watch D.C. to run a Homicide Watch project in Chicago. Sun-Times Editor-in-Chief Jim Kirk said the launch was "about engaging the reader." I don't know their original intention, but Homicide Watch has not fit easily into the Sun-Times main digital properties. The Sun-Times has chosen to link to their Homicide Watch project from the "Chicago News" section of their website's menu, but it’s not tightly integrated with the main site. Articles covering the same incident in the Crime section do not link to Homicide Watch, and vice versa.

Engagement

If a structured journalism project isn't prominently featured in an existing, high-traffic publication then it must somehow attract readers on its own. Fortunately, the data-rich nature of these projects lends itself to attracting traffic directly from Internet searches, what marketers call "organic search traffic." Homicide Watch D.C. was an independent project, yet they ended up attracting 330k visitors per month. Co-founder Laura Amico explained to me that "traffic was mostly organic at first; then we started getting a lot of direct traffic as people returned to the site to check on cases."

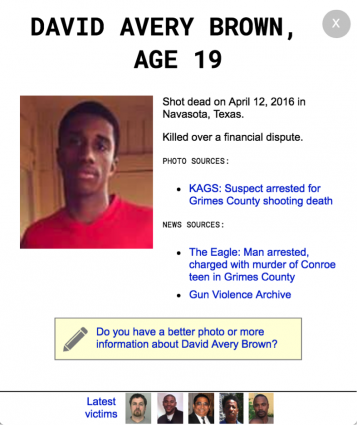

At Gun Memorial, we posted more than 20k distinct web pages within the first three months of launching the project, each page giving some basic information about a death that occurred in the past few years. This gives us plenty of opportunity to appear in Internet search results. For example, when a family member or friend googles a victim's name, a Gun Memorial page is likely to be on the first page of results. Getting to the first page involved some basic search engine optimization; search engines give a high rank to our pages because the victims' names appear in the page url and because our content is engaging enough to keep visitors on the site for several minutes rather than letting them quickly "bounce" back to the search results. Search engines also like that our pages all load quickly and are mobile-friendly.

But how do you get readers to come back to the site? For Homicide Watch D.C. the answer was to build a community.

Community

Homicide Watch D.C.'s Amico told me that each of their cases created a community around it, including people who knew the victim and the suspect — anyone who wanted updates on the court proceedings. This included not just family and friends but also people like the nurses and doctors who treated the victim.

She explained, "You should identify your audience and then address their pain points. Homicide Watch's readers were trying to navigate a very confusing court system. [Part of] Homicide Watch's mission was explaining the court process and giving readers some agency within a process that they typically felt disadvantaged by. We allowed people to attend court dates."Are journalists ready and willing to think more like software startups — in terms of identifying and solving pain points, not just informing or entertaining readers?

Homicide Watch D.C. was actually solving concrete problems for their readers and affecting their lives in a real way. Are journalists ready and willing to think more like software startups — in terms of identifying and solving pain points, not just informing or entertaining readers?

Social media

Another way to engage readers on a recurring basis is to win their "like" or "follow" on social media. The Counted has more than 30k followers on Twitter and its accounts are managed by The Guardian's social media staff. They post updated statistics nearly every day and they highlight noteworthy new cases and quote from articles related to the project.

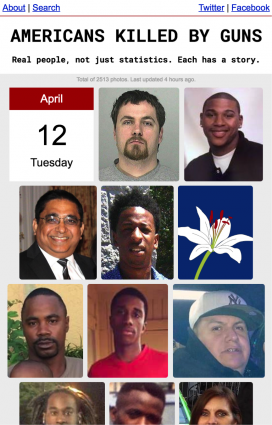

Similiarly, Gun Memorial posts daily photo collages to social media which shows the faces of 10 to 40 new victims who were added to the database. Followers can learn more about each victim by clicking the post. Social media acts as the main return path for the reader in our ideal reader journey:

- A Google search leads a new reader to the page of a specific victim.

- A banner of "latest victim photos" leads the reader to the project index to see more victims.

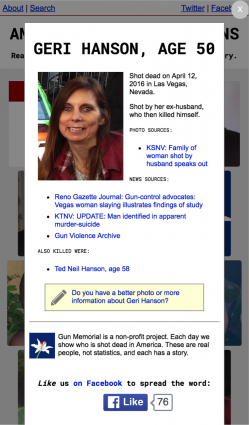

- After viewing the details of maybe a few dozen victims, we hope the reader will click the "Like us on Facebook" to get updates. This rarely happens. ?

- Our daily updates appear on the reader's Facebook timeline and hopefully that will cause them to re-visit the site or share our updates with their friends.

An alternative "call to action" in step three might be to sign up for an email list. In that case, a weekly recap email would be the return path for the reader. Thus, for independent projects, the journalist must act as publisher, community manager, social media maven, and digital marketeer.

Maintenance

We've said that structured journalism projects tend to be independent in nature and they have to build their own audience and following. Building your readership, search engine ranking, and social media following all take time, so you have to be committed to running the project for a while.

Given that long-term commitment, it is wise to invest developer time into creating tools to support your daily reporter workflow. We heard this from both the Homicide Watch and The Counted. In another interview, Amico said, "Having the platform speeds up my workflow by creating a pattern out of my work. So, when a case comes in before I’ve had my coffee in the morning I can pretty much operate on autopilot." Lartey told me, "For the first few months, we had 3 reporters working full-time on the project — updating the database and writing long-form stories. The interactive/technology team probably spent even more time at first. Now one reporter can typically do the daily update in a few hours." Gun Memorial also has a reporter workflow, and in my experience building that workflow is best served by an iterative development process that takes new feedback from reporters on a regular basis.

Crowdsourcing

If spending months or years of your time reporting on a single project sounds daunting, crowdsourcing the reporting may sound like an appealing option. However, there's no free lunch here; crowdsourcing adds new software development, recruiting, moderation, and quality-control work.

EBWiki is a crowdsourced publication that tracks cases when people of color were killed by police. Just like Wikipedia, anyone can edit cases on the site or create new cases. I spoke to its founders, Mark Nyon and Darius Goore. Nyon said, "We spend about 10 hours per week [on the project], which is sustainable. Regardless of the time we spend, using Wikipedia as our model, the more crowd contributions, the greater our bandwidth becomes. ... Only administrators can delete cases. Everything else is fair game for logged-in users." Anyone can view a history of who made what changes, so any fishy edits or vandalism should be easy to spot and reverse.

Building a community around their project also allows EBWiki to fulfill a role that the Guardian and Washington Post projects do not. Nyon said, "Our specific focus is more longitudinal, looking at the initial incidents as the start of a multi-year long process involving legal proceedings, community efforts, and policy reforms, etc. We also see ourselves as eventually going beyond informing users to helping them organize around these events and ultimately act constructively to address the underlying structures to stem negative behaviors depending on bias."Reader contributions are not just about sharing the reporting workload; readers give you new perspectives and access to the private, offline world of those affected by the story.

Crowdsourcing certainly seems to get easier as traffic on the site increases because more traffic means more opportunities for contributors to add information and make corrections. That's why Wikipedia articles on popular topics are generally of higher quality than those covering obscure topics. There is a bit of a chicken-and-egg situation here, so one should expect to "bootstrap" any crowdsourced project by starting with one or more very-dedicated contributors.

My experience with Gun Memorial suggests that it's easy to add mechanisms for the community to filling-in missing pieces of information. In some cases my own efforts to find a photo online for a victim will fail; such a victim's page will include a form allowing readers to submit a photo. These sporadic contributions provide new content that I would never find in any reasonable amount of time. Reader contributions are not just about sharing the reporting workload; readers give you new perspectives and access to the private, offline world of those affected by the story. However, for daily beat reporting, the grunt-work-on-a-deadline that drives the site, it's not clear how to get volunteers regularly involved.

Conclusions

We know that structured journalism creates a new experience for the reader. They are given more freedom to follow their own path through the story and to examine underlying data. But it's also a drastically new environment for the reporter. A single project may involve significant custom software development efforts for both the reader-facing presentation and for tools to support the reporter's workflow. To be really successful, a community will have to be built around the project, which involves identifying an audience and its needs, branding, grassroots marketing, and social media campaigns. Finally, you'll have to somehow sustain reporting and distribution for the project for at least a few months (if not years) for the project to really reach its full audience.

You may ask: is it really worth the effort? That depends on your goals and the alternatives. Large-scale structured journalism projects like Homicide Watch and The Counted change our macro view of an issue and can have big outcomes. FBI director James Comey cited The Counted and the similar Washington Post project while lamenting the federal government's lack of data on police fatalities. In the same week, U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch announced a pilot program to track police killings.

Structured journalism projects don't just tell a single story, they can tell the whole story and they can remain relevant for many years after they're discontinued. Of course, this assumes that the publisher keeps the website running and working, a task that every publisher fails at to some degree and something that should be the topic of another article.

About the author