Data. Interactive. D3. X charts and Y graphs that explain Z. I feel that we’ve reached a point where “interactive” has become an empty buzzword in journalism. It’s amazing how quickly interest and adoption of news apps and data visualization has grown in the last few years (just look at the sheer size of this year’s NICAR conference), but as interactive and data-driven journalism becomes more pervasive, we also need to reexamine the meaning of “interactivity” itself and, more importantly, what it means for different roles in the newsroom.

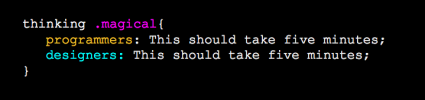

The question of interactivity and collaboration was a consistent theme across the conference. Ashlyn Still’s lightning talk argued that not every story needs a cool interactive. “Don’t force visuals solely for the sake of visuals.” Lily Mihalik and Anthony Pesce talked about how to bridge the gap between designers and developers in their lightning talk, particularly when it comes to language. The “work your magic” language transforms the efforts of any news apps, data or visuals team into a black box. These teams are not wizards or magicians — they’re storytellers and subject matter experts. Their work should not be an afterthought. “Oh, can you make this interactive?” at the last minute rarely produces a satisfying result for anyone, including the reader. Instead, Mihalik and Pesce advise us to learn to “speak each other’s love language,” whether that’s learning how to use Github or learning the importance of three extra pixels to a story’s visual design.

I also attended a panel on "Thinking about interactivity" moderated by Robert Hernandez where Mariana Santos, Trina Chiasson, and Melissa Bell discussed their organizations’ different approaches to making pieces “interactive” and answered questions about how to execute such projects.

When do you know a story is worth the time and resources to make it interactive?

“If editorial doesn’t have the time or space to think about design and development, it won’t be worthwhile to put resources into a project,” Bell explained, emphasizing that prioritization for both development and editorial is crucial to ensuring a strong collaboration. For data, Santos and Chiasson think heavily about whether there’s a strong narrative that can be extracted and whether readers can “find themselves in the data.” Chiasson used a piece by BBC News about the world’s population reaching seven billion as a simple example. By allowing the reader to enter in their birthday to see where they fit in the seven billion, the interactive provides a mix of personalization as well as a broad view of the data.

How do you guard against too many cooks?

Bell advised people to organize the moving parts of a project and think about who is responsible for different components. Daily meetings can be helpful just to identify problems and discuss how each person’s job overlaps with others’. Everyone is an expert on something, whether it’s reporting, video editing or programming. Focusing on what each person is bringing to the table helps delegate decision-making and pinpoints opportunities for collaboration.

How do you say no to an interactive request without burning bridges in the newsroom?

Santos and Chiasson note that there are times when “interactivity” is appropriate and times when it is not. Other times, there simply may not be the time and resources to take on a new project. The challenge comes when an enthusiastic journalist contacts someone on the interactive team after a story has been reported and written and simply asks for some of that interactive magic.

Instead of turning down such a request without explanation, Santos advises bringing said enthusiastic journalist into their thought process. What purpose is interactivity serving? How does it enhance the story? What aspects of the story can be translated purposefully with interactivity? By asking these kinds of questions, we can help people reframe the way they think about interactivity. It should be something that reporters and editors actively think about even in the early stages of a story, not just an add-on at the very end.

Should reporters learn to make their own stories interactive?

No one should be pressured to become a coding expert just because they work on big features or wrangle big data. There are so many amazing tools out there for reporters that can help them to easily create their own interactive elements — why not take advantage of these resources? “The goal is to empower people who may not have backgrounds in statistics or programming to dig in and get a sense that they can create things that are interesting with data,” said Chiasson.

However, knowledge sharing can be helpful for reporters who are interested in having more control of the presentation of their own stories. Santos challenged the idea of creating “one-off” projects, which are unlikely to be worth diving deep into a certain technology for budding journalist-turned-coders. Instead, journalists should aim to create “persistent resources” and build skill sets that can be carried over from project to project.

About the author