When we think of data, we almost always think of computers. But when it comes to data that was created before the digital area — handwritten notes, ancient maps or printed documents, for example — nothing beats human eyes to quantify and verify. And when many human eyes are needed, journalists have the option to crowdsource their data.

At MozFest this weekend, Mike Tigas of ProPublica and Jeremy B. Merrill of The New York Times facilitated a session that touched upon four projects leading the movement in crowdsourcing data. Here's a look at a few projects and why people want to get involved:

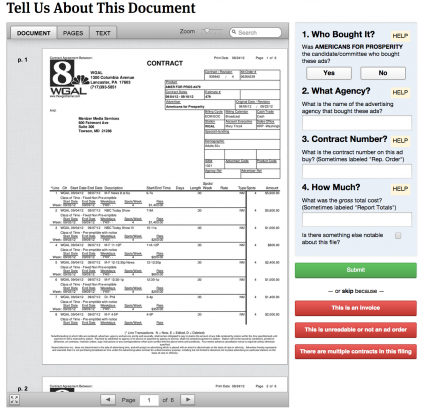

Free the Files

ProPublica’s Free the Files tool began crowdsourcing back in 2012 when it asked users to “free a file” about political TV ads, by recording the advertiser, agency and gross total dollar amount spent on an ad. In the time since the project’s launch during the 2012 elections about 18,000 documents have been "freed" out of more than 43,000.

It takes two reports of identical information to verify a file’s data, according to Merrill. Once this occurs, the file’s information has been freed, and ProPublica publishes the information.

NYPL's Building Inspector

The New York Public Library crowdsourced maps in 2013 via a project called Building Inspector. The tool asks users to identify colors, realign building boundaries and input addresses of 1850s New York City. By relying on the input of users to verify information, the data stored in these scanned images of discolored maps can be used with modern cartographic tools.

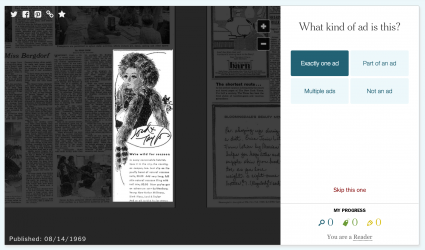

Madison

Additional historical information from New York City has made its way to the crowdsourcing platform via The New York Times’ Madison project. Madison asks users to click one of several buttons to indicate whether or not the depicted image is an advertisement or some variation of. Although the digitization of The Times’ archives has largely focused on editorial, advertisements can be a telling indication of history as well. With Madison, The Times intends to unlock this data.

CrowData

Another crowdsourcing data tool, CrowData, was released this year and is available on github. CrowData comes out of an initiative by La Nacion called VozData, which uses the public to verify records released about political spending, much like ProPublica does with Free the Files.

Why do readers contribute to data projects?

Free the Files and VozData incorporate gamification into verification by asking users to log in and displaying a leaderboard of the top contributors. With gamification, “you make people more engaged with some data that they otherwise would maybe never have looked at,” Tigas said.

Projects like Free the Files are alternatives to paying many people for hours of work pouring over data. Because they rely on free work from the public, the verifiers must be interested in the information and believe that the news company is going to do something beneficial with the data.

Merill said that an ideal case for crowdsourcing data is one that provides an exchange that goes both ways. “Where you learn something meaningful about the world that you didn’t know before by doing this,” he said.

Others feel a personal connection to the projects. “There are people who are really interested in their neighborhood histories,” Tigas said. “And so they get something out of [Building Inspector] because they learn what their neighborhood looked like.”

“There’s a whole segment of readers that are really interested in being involved with the news that they read,” he said.

About the author