On Friday, FiveThirtyEight announced that Dhrumil Mehta (a former Knight Lab student fellow) would be joining their team as a database journalist. It was fun news for us to hear, particularly when you consider that a year and half ago journalism wasn’t even a small part Mehta’s career plan.

At the time, Mehta was a senior here at Northwestern and six months from completing a bachelor’s degree in philosophy (with a cognitive science minor) and a master’s degree in computer science.

As a student, he'd built a few websites for non-profits and civic organizations, but he wasn’t quite sure how to take his technical skills and apply them to a job he really cared about.

“I had always felt out of place in computer science,” Mehta said. “I always liked making things, but I didn’t enjoy making just anything. I wanted to do something to make people’s lives better.”

At the time, he talked frequently about following the well-worn computer science graduate’s path from school to big West Coast technology firms — Microsoft, Amazon, Oracle, etc. — before finding a way to do work he really loved.

And then he joined the Lab as a fellow, he worked on a few projects, and joined the team for the trip to NICAR's 2013 conference in Louisville. And attending the NICAR conference, it turned out, would make all the difference.

“What was most striking to me was the casual manner in which journalists at NICAR spoke about the truly huge impact that they were having on the world,” he wrote at the time, “and how powerful use of data can be in showing the vastness of any given problem and spurring people to act to resolve it.”

At NICAR, he said, he found people he wanted to be and be like.

He also caught the interest of USA Today’s Paul Overberg and Jodi Upton, who could see the potential in an academic project Mehta had been working on to become a useful new news app.

The political rhetoric project

Inspired by the linguist George Lakoff and his books Metaphors We Live By and Political Mind, Mehta started to think about how politicians use metaphors to frame political topics in speeches. He wondered if he could use data and natural language processing to figure out not only how politicians frame certain topics, but how they frame topics given party affiliation, and how framing changes over time.

(NOTE: There’s a fair amount of detail down below, but also check out the project’s blog and the academic abstract.)

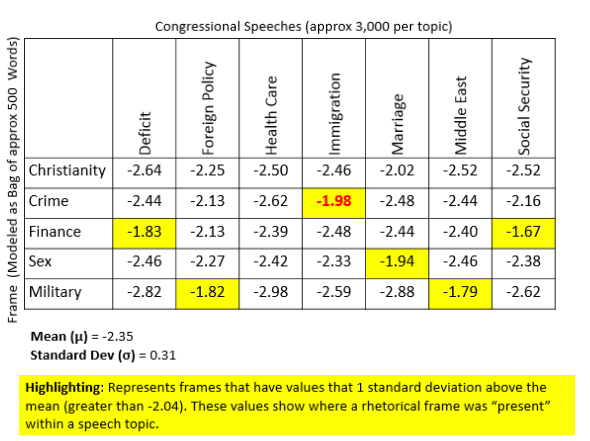

Working with congressional speech data from the Sunlight Foundation’s Capitol Words project, he built an algorithm that analyzed 10,000 speeches in each of seven categories: national deficit, foreign policy, healthcare, immigration, marriage, the Middle East, and Social Security.

Using a TF/IDF weighted multinomial naïve Bayes classifier (commonly used to filter spam), he found that he could reliably classify a both a speech’s category and the party of the speech giver.

It was an interesting project, but Mehta wasn’t content to merely classify speeches. Instead he fed the classifier a set of rhetorical frames culled from WordNet, a lexical database of English words that are grouped into sets of “cognitive synonyms (synsets), each expressing a distinct concept.”

Mehta used Wordnet’s synsets to build 500-word frames related to specific topics: Christianity, crime, finance, sex, and military.

The idea was to figure out if a particular frame was present in the rhetoric of the seven categories he’d chosen (national deficit, immigration, etc.). So instead of feeding the classifier new speeches, he fed it frames.

He found that words from particular frames were highly correlated with speeches about particular topics. For example, he found speeches on immigration often included words related to crime.

Digging deeper (and with the help of a binomial classifier trained only on immigration speeches) he found that Republicans used crime rhetoric much more often than Democrats when talking about immigration.

Though the project was academic, it caught the interest of Overberg and Upton who Mehta met at NICAR 13.

Together, they began thinking about how Political Framing might go from an academic project to a functional news app that would help journalists find news.

What if, for example, Political Framing could show you when a party’s — or politician’s — rhetoric on a certain issue changed? Could Political Framing cross-reference changes in speech with campaign contribution data to alert reporters to a rhetorical change following a large campaign contribution?

Last week, Mehta and his teammate (and current student fellow) Al Johri, took the first step toward finding out with PoliticalFraming.com, which seeks to help reporters find trends in congressional rhetoric. They’re currently looking for alpha testers.

Meanwhile, real life

Despite the interest in Political Framing and taking significant detours in to journalism and civic technology — an internship at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, to name one — he also managed to graduate and land an engineering job and moved to Seattle last fall.

But journalism and his civic technology projects kept pulling. Political Framing, in particular, “turned out to be something much bigger than I thought it would be,” he said.

He presented his work on the project at NICAR 2014 and will do the same at the American Political Science Association’s conference later this year.

He also happened to see a job earlier this year on the NICAR-L listserv that proved irresistible, "database journalist, politics." He reached out to Andrei Scheinkman, deputy editor and director of data and technology at FiveThirtyEight, about the position and was eventually hired.

Despite his accomplishments, journalism is a new track for Mehta.

“I’m totally new to journalism,” Mehta said. “I’m really nervous and excited at the same time.”

In the end, the big tech firm job was nice, but his heart wasn't in it.

“It may sound simple but I wanted to do something that is good for people,” he said.

About the author